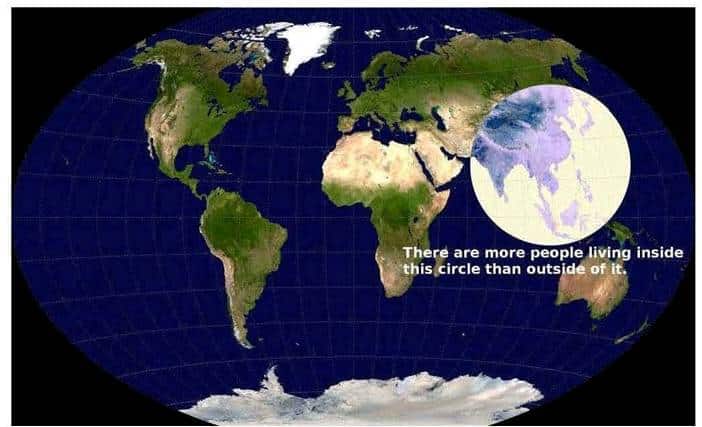

The map you see on this page has been widely circulated among professional investors, and it tells an astonishing story. The circle encloses less than an eighth of the world’s total land mass, but it includes more than half of the world’s population. Within that circle are the world’s two most populous nations: China, with 1.35 billion people and India with 1.22 billion, plus countries that rank 4th in population (Indonesia, with 251 million), 8th (Bangladesh, with 164 million), 10th (Japan, with 127 million), 12th (Philippines, with 106 million), 13th (Vietnam, with 92 million), 20th (Thailand, with 67 million), 25th and 26th (Burma and South Korea, both with around 50 million). Also in the circle: Nepal, Malaysia, North Korea, Taiwan, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Laos, Mongolia and Bhutan.

Add them up and you have 3.64 billion total citizens, or roughly 51.4% of the world’s people.

So the immediate question may be: why isn’t my investment portfolio 50% invested in this region of the world? Why isn’t my portfolio weighted by population?

The answer is simple. While this circle represents the world’s center of gravity as measured by people, it also surrounds some of the least efficient places to deploy your investment resources. Take China, for example, where the same company’s shares trading on the Hong Kong stock exchange routinely cost two or three times more than shares trading in Shanghai, where Chinese residents buy and sell their stocks. Both shares carry identical claims on assets and profits.

Why the difference? Chinese residents invest through so-called A-shares, which most foreign buyers are forbidden to trade in. The rest of us buy B shares trading in Shanghai or Shenzhen, or H shares traded in Hong Kong, or red chips if the companies are state-owned, or P chips if the Chinese company is incorporated outside of the mainland, or N shares for certain Chinese companies listed on the U.S. trading floors. These other share classes share one thing in common: they trade at higher multiples than the relative bargains offered to Chinese citizens. China has granted several foreign firms and investment groups permission to own limited amounts of A shares, but it’s not easy to know, from the outside, which firms have an inside track.

Another problem with investing in China is transparency – or, more precisely, the lack of it. U.S. based public companies are required to disclose their financials in great detail, and large accounting firms are required to audit and sign off on the accuracy of those statements. In China, accounting standards run from lax to nonexistent, and the Chinese government can forbid foreign access to the books and records of any company on the theory that this might reveal “state secrets.”

Enough about China, what about India? Here again, the government forbids non-Indian investors to buy shares of publicly-traded companies. Only six of the 30 companies listed in the BSE SENSEX index – the Indian equivalent of the S&P 500 – allow shares to trade on the U.S. exchanges. A few Indian-focused exchange traded funds are allowed to buy shares.

Indonesia’s stock exchange, meanwhile, could be charitably described as “undeveloped.” Currently, it facilitates trading in just 462 listed companies, which have a combined market value of $462.78 billion, almost exactly the current market capitalization of Apple Computer. Trading activity on the Jakarta stock exchange makes up less than one tenth of one percent of the global investment flow.

Of course, the Japanese stock market is large and robust, but investors in Japanese stocks have been less-than-thrilled by their performance since 1991. The Nikkei 225 Stock Market Index peaked at just under 40,000 22 years ago, and now is worth about 12,500.

There is no question that eventually the people living inside of this interesting circle will start punching their weight in the global economy and provide thriving investment opportunities that will conform to more stringent world standards. However, until that transformation, for now, a prudent investor avoids investing by population. You should have some money in the emerging economies and watch closely the new developments in Japan, where the prime minister may be shaking the economy out of a decades-long slump. There may come a time where wisdom indicates to put more than half of your investments into eastern Asia, but that time is not now.

Sources:

http://www.forecast-chart.com/historical-nikkei-225.html

http://seekingalpha.com/article/829631-how-can-americans-invest-in-indian-stocks

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jakarta_Stock_Exchange

http://www.advfn.com/nyse/newyorkstockexchange.asp