You may have read that the U.S. stock market was buoyed to new record highs by news that Japan was stimulating its economy. And you might have wondered about the connection. As you may know, the US has the world’s largest economy by Gross Domestic Production (GDP) at around $17.4 trillion per year, China $10.3 trillion and Japan $4.8 Trillion. So the third largest economy by GDP is important for the health of the overall Global economy.

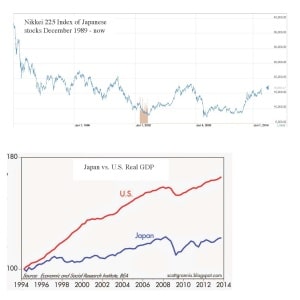

Over the last 25 years, the Japanese economy and stock market have been remarkable stories, but not in a good way. As the chart shows, if you had invested all your retirement money in Japan’s Nikkei 225 Index in December of 1989, and held stoically during the long downturn, your patience would have been rewarded with overall losses of more than 50%; that is, your $1 million nest egg would be worth somewhere around $450,000. The second chart shows that Japan’s real economic growth has been anemic for the past 25 years, especially when compared with the U.S. The country has experienced chronic deflation, low consumer spending, repeated recessions, more government debt per unit of GDP (by far) than any other nation–and, more recently, labor shortages and low female participation rate in the labor force.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has vowed to fix all of this with heavy government intervention in the markets. His so-called “Abenomics” policies are flooding the Japanese economy with cash in hopes of stimulating inflation, raising government welfare and public works spending to record levels, lowering corporate tax rates, changing childcare policies so that more women will enter the workforce, encouraging free trade, deregulating many protected industries (notably farming and healthcare) and lowering the barriers to foreign direct investment.

How is it working so far? As you can imagine, special interests are fighting against lowering trade barriers and corporate reform, and consumers are waiting to see signs of inflation before they open their wallets. The Japanese economy still seems to be stuck in neutral.

So when the Bank of Japan, just a few days ago, announced that it was going to buy $721 billion worth of Japanese bonds each year, in a new initiative to create new money for the economy, global traders sat up and took notice. They were betting that, finally, the Japanese government had found the formula, and the resolve, to shock the zombie economy back to life. Even so, it’s hard to see why U.S. stocks would cheer the news. Japan only buys an estimated 4.5% of all U.S. exports, so even a big boost is only modestly good news for U.S. companies. In fact, you could argue that a resurgent Japanese economy would create more competition for U.S. exporters.

Is Japan now poised to return to the global economic pre-eminence that the country enjoyed during the 1980s? Probably not. At best, Abenomics and the new stimulus might lead Japan back to a more normal economic growth pattern, and allow its long-suffering shareholders a chance to finally get the returns that investors in virtually every other country have enjoyed. Meanwhile, 25 years of economic stagnation and declining markets may be a cautionary tale for the U.S.. If the central bank and the government don’t take forceful action when the economy goes into a severe funk, the longer they wait, the harder it is to revive the patient.

Sources:

http://www.tofugu.com/2014/09/19/the-3-arrows-of-abenomics-explained/